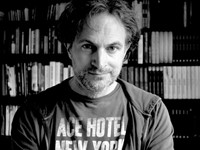

Marcus Sedgwick

About Author

Marcus Sedgwick was a full time author who died unexpectedly in November 2022. He was 54. He grew up in Kent and had been living in the south of France.

Marcus's first novel, Floodland, won the Branford Boase Award for the Best Debut Children's Novel of 2000 and he went on to write more than 40 books for children and adults. His books won several awards, including the Book Trust Teenage Prize for his YA novel, My Sword hand is Singing, and the 2014 Michael L. Printz Award for his novel Midwinterblood. He also received two Printz Honors, for Revolver in 2011 and The Ghosts of Heaven in 2016, and his books have been shortlisted for the Guardian Children's Fiction Prize, the Blue Peter Book Award, the Costa Book award, the Carnegie Medal and the Edgar Allan Poe Award.

Marcus also co-authored graphic novels with his brother, Julian Sedgwick, including Dark Satanic Mills and Voyages in the Underworld of Orpheus Black. When he wasn't writing, he enjoyed listening to music and he played the drums.

Interview

Ghosts of Heaven (Orion)

2015

Marcus Sedgwick is the award-winning author of YA novels, books for younger readers, picture books and graphic novels. He spoke with Graham Marks about his novel, The Ghosts of Heaven.

1. The Ghost Of Heaven has the feeling a project that's been a very long time coming - is that true?

We've spoken in the past about the way I work, and how I spend most of my time thinking not writing, and that I only write when I am ready to write. In a way, when someone asks me how long does it take to write a book I always hesitate and say, "Well, what do you mean exactly?" If you're including the thinking time, then this book is the longest one ever because I first had the thought about spirals when I was a student in Bath, so I was about 20, 21, something like that. I wasn't even a writer then, but it's just one of those things that has been in the back of my head ever since. A long time.

2. I wondered where your World Book Day book, Killing the Dead, fitted into the scheme of things. It's a standalone story, but it is also got very definite links to Ghosts of Heaven.

So, Ghosts of Heaven came out of a two year period of writer's block, of not knowing what to do or what to write, and I was feeling a bit fraudulent…I had been trying to do this thing about spirals, but then I started to get glimpses of what the different bits of the book could be. I quickly decided that I wanted to write another portmanteau novel, with different bits to it, because I enjoyed doing Midwinter Blood and I thought it would be fun to do it again sometime.

I started developing the four stories in tandem, but then towards the end of that process, almost when I'd finished those four - and I had very consciously been nudging one along and then another, trying to make the one that was behind catch up - right towards the end of that process I started getting ideas for a fifth story, which was a pain; but I thought leave it be.

My idea was, at some point, that I would just write Killing the Dead for me, or publish it myself, or see if Orion wanted to do something with it. Then the World Book Day opportunity came along so that one of those perfect little things. Of the four stories, I do think it's probably the one that stands alone the best. That was one reason why I left it out, and also because it wasn't originally part of the conception.

3. I felt like there was…the only way I can describe it is, I felt that there was a 'butterfly' point of view in Killing the Dead, as if the narrator was a ghost floating over the story, observing. Was that the effect you were going for?

Yes, very much…very nice you said that. It takes another writer to spot these things sometimes, doesn't it. I was very much trying to work with a slightly different narrative voice than I have done before.

Because Ghosts of the Heaven effectively has four different narrative voices - there's the verse one, and then the diary one - and some of the things I have been reading recently are [the kind of thing] you know you're taking in and you know it's influencing your writing style.

A book I read a few years ago, which many people would say is not a great book, is called Ritual, by a guy called David Pinner. It was written in the 60s, and is the novel that the original Wicker Man film was based on, [although] they ditched almost everything in the book except the core concept of a policeman investigating a murder. The book got completely slated at when it came out, but I read it towards the end of this last period of writer's block, [when I] had this feeling that I'd fallen out of love with reading and hadn't read anything that had amazed me in a long time…I was thinking, "What's new?".

Every couple of years for the last six years I'll read a book that just makes me remember why I love reading and gets me excited again. Pinner's Ritual was one of those books, and I am not pretending it's the most amazing thing ever, but there was something about the prose style that excited me. In a way, our sense of what a narrator is has changed since the time of Flaubert, or Proust or whoever you claim invented the novel. That sense that you are an objective third person narrator, but actually let's not pretend you can't be personally involved, too, is what I was trying to do in Killing the Dead.

4. When that thought occurred to me, it was as if I'd joined the narrator above the story, which is in an interesting perspective.

I don't know what you think about this, but there is kind of a [editorial] paradox, because what we get told all the time is that you have got to make your readers relate to your characters and they've got to be right there. But I've read a number of books that did the complete opposite, where the characters were really distant…like a weird little novel called The Vampire Of Ropraz; it's a Swiss novel, in French. It's very loosely based on a crazy serial killer who was running around at the end of the 19th century and committed a horrible series of murders, and who became known as the vampire of Ropraz.

The novel is very short, but it really feels like you're reading a newspaper report. I was thinking [as I read] that this shouldn't be working, I shouldn't be caring but, paradoxically, it worked really well. I think some of the things we hear repeated as mantras by the industry, about how we're supposed to work, sometimes you can put a bunch of dynamite under them. If you find yourself being corralled by the points of view of people who are great editors, but who don't write, that's where you have to be totally clear about what you want and need to do.

What worries me, particularly in the YA world at the moment, is everyone is telling everyone else what a YA book is. I think that's particularly sad because, for me, it's the exact opposite of what a YA should be - which is, like the teenage brain, as experimental as possible.

5. If you hadn't used Killing the Dead as a World Book Day book could you have put it into Ghosts of Heaven? It seems like it would fit quite neatly in your timeline after The Easiest Room In Hell.

It would do, but I felt like I wanted four very different stories and if I'd put it in, I'd have had two set in America, 40 years apart, and the other thing is that I'm trying to play a little game in that perhaps the times when you think the stories are set aren't when they're set. I mean that particularly in reference to the first and fourth parts, as they're printed in the book.

I also think five stories of about this length would become unmanageable. The way I saw it… [picks up a small, four-sided object] …this tetrahedron is a way of connecting four planes so they are all touching each other. And that is what annoys me about a book, that it has to have a physical, printed order. In my mind a tetrahedron is the shape of this book, and if I had added a fifth story it would have been made some impossible shape that only aliens can understand.

6. You say there are 24 different ways you can read the book; what order did you write them in?

I wrote them in the order in which they are printed, because, for me, there were two important orders in the book and that is one of them. I don't know how you work, Graham, but I have come across writers who write the most exciting bit of their book first, or the end first, or maybe they write the first idea that they had first. Then they spend seven months playing blocks with it. I think it is a hard enough writing a book, why make it even harder by then second-guessing the way in which it will be read?

7. I would like to talk about this book the way in which the four parts are presented, starting with the opening story; Whispers in the Dark, which is actually a 100-page epic poem, introducing us to some of the major themes in the book: death, spirals, belief. Why did you decide to tell a story, which I think is set in prehistoric times, in this way?

On the face of it that is where it's set; I haven't specified, but let's say it's kind of late Neolithic period. It's said formal writing systems are five, six thousand years old, that we can be sure of, and then there are proto-writing systems which come before that - marks on rocks, symbols. I don't know if it's writing or not, but I wanted to try and use the moment in which someone makes that connection, with the word to the mark. And that is, to me, when writing is invented. I wanted to set Whispers in the Dark in that world.

The next thing I thought was that I wanted this to feel authentic…I think I was scarred by films like One Million Years BC when I was a kid, they always had names with lots of Ks in them and it's all really brutal. We don't know that, for all we know the language they were speaking was a very lyrical, beautiful language, so I thought "How can I tell this story?". And it comes back to what I was saying about distancing.

I decided to use the blank verse as a way to try and be authentic, in a sense that it lent a distance and made it feel remote and 'other'. I limited the language to these really simple, reported verbs because I didn't want to have names and I didn't want to have any dialogue because it would have just felt ham-fisted to me.

The other really important thing is that there has been this debate, yet again, about whether a YA book has to have a YA protagonist. The female character in Whispers in the Dark is my only YA protagonist in the whole book; I figured, OK, we're set in the Neolithic, say - what is life expectancy? We know that some people did live to be 60 even 70 years old at the time, but the average was much, much lower, maybe 20 years old, on average, because of disease and accidents. Therefore, the bulk of the population would have been teenagers.

Not only that, but I'd really wanted to do something with cave art for a long, long time and some of the research that's been done recently showed that not all of the cave art was done by men, some of it was done by women, some of by children. I thought that was really interesting. And then I thought that the constant representation of teenagers, in the media, is that you only hear about them if they're pregnant and under-age, doing drugs in the park, mugging a granny or whatever it is.

I found that bias [in a lot of places]… I'd started getting a magazine called The Cultural Anthropology of Archaeology, and even in there there was an article about cave art, saying some of it is was done by teenagers, and then in the next breath going on to say it was basically teenage graffiti [because] they're drawing penises and breasts and all of that. I thought even there, in the academic world, they're taking that bias on, given that we now know a lot about how the teenage brain works. We know it works a bit differently, bio-chemically, and in all of the ways that drive you mad as a parent - all the staying up late, the experimenting, the not doing what you said you would do - we know that's all because of the different way the teenage brain works.

So perhaps teenagers aren't acting this way because they like being difficult, perhaps it's because evolution found it useful to have this experimental stage in our development. I think you can make a very good case for arguing that teenagers are the reason we are the species we are. That thought makes me very happy for some reason. Maybe because it explains some things about ourselves, recalling the person you were at that time, going through the same period. I think that's a brilliant thought. I just think evolution doesn't leave anything behind that wasn't there for a purpose. You could say the appendix, but it was probably doing something wonderful once upon a time.

8. I did wonder - with Whispers in the Dark being a long form poem and poetry being a theme throughout all five stories - if you have always written poetry or did you have to 'become' a poet for this book?

I haven't always written poetry. I was, I think like many people, really scared of poetry for a long, long time… the last time you are really allowed to approach poetry, unless you are doing English 'A' level, and I didn't, is in primary school. And what do you know about poetry after that? Yes, I know there are poets I liked - Robert Graves, for example, I always loved his stuff - but I was scared to ever try it.

What changed was that a few years ago I started learning Swedish, as I was going to Sweden, and I wrote some poems in Swedish…because I figured I don't know how to speak Swedish properly, and I don't know how to write poetry properly [laughs], so therefore I may as well join the two things together and see what happens.

It sounds a bit silly, and I didn't write that many [poems], but it did break my fear of it and I have been writing poetry ever since, but I haven't really used it in books anywhere, apart from some tiny little bits in some of the other novels. I just decided to stop judging myself and have the freedom to try.

The second story, The Witch in the Water, is set at a time when poetry was the pre-eminent literary form, which it certainly isn't now, so are you hoping to increase its relevance by using it quite so much in this project?

I think I hoped to show that books can be as free as you want them to be - and especially that books for young adults can be as free as you want them to be. It's a funny thing about the poetry… I've spoken to a few librarians and teachers [about the book], and they've said some of the kids were a bit put off because a poem is first thing you see in the book, and I was a bit reticent about that. But I discussed it with my publisher and she said "No, let's just be bold, let's go straight into the poetry".

If you hear it read out loud and you can't see the stanzas, because it's blank verse, it's probably not so scary; so it might work better as an audio book. And I don't know if I am trying to encourage poetry, but I think I am always trying to encourage the idea that books can be as remarkable as anyone can make them.

9. That story, The Witch in the Water, seems to be mainly about beliefs, both religious and magical, and the power they hold over people. Do you think human beings will always need gods to believe in or has Sentinel Bowman from the last story, The Song of Destiny, gone beyond that need?

You are absolutely right, that is a question I'm trying to ask, and I always think it's the writer's job to ask the questions and not provide the answers. I seriously think doing that drives some people crazy; I think there are two types of readers, I think there are readers who want to be told and there are readers who want to be provoked to think. This is a book for the second person [laughs]. Therefore the book is mystifying a few people, but I think I have to take that on the chin because I wasn't trying to answer questions.

One of them is a very big issue: will we ever evolve to the point where we no longer need to believe? I think it is interesting, if you look at the secularization of the West, certainly the UK has a lower level of general belief than say the States - and I heard that apparently the Czech Republic is the most secular country in Europe, if not the world. I think it is interesting to follow those developments. If you look around this little village [I live in], behind the house is a 1,000-year-old church…30 years ago, even 20 years ago, that would have been full of people on a Sunday and now three people go and the vicar is shared with three other villages. Then you look at the world, and all of the religions of the world, and you think well, no, we are still a world of beliefs.

10. You use a quite antiquated vocabulary in The Witch in the Water, which stopped me in my tracks a couple of times and I had to go look things up; did you have to do a lot of research for this story? For all of the language and the rites?

I did some, partially because my second book, all those years ago, Witch Hill, was a witch story and I had done a load of really accurate research for that one. When I came to do this book I decided to wing it a whole lot more, so some of what I used was left over in my brain, and some I went back and reread [the original research] material.

To me the single most important thing is the feeling of a witch hunt - whether they were the American ones or the British ones - that combination of fear, claustrophobia and violence. Once it starts in that little world you are in big trouble. I read one of the classic accounts of the Salem witch trials, which is called The Devil in Massachusetts. It is the kind of book that we don't get so often now because it is a nonfiction account of the witch trials, but it's written in a writer's way, in a very prosey way. It really got that awful atmosphere I was just talking about and I wanted to re-instill that kind of feeling in myself.

You asked about the rites and I have always read a lot of books about folklore, so I was drawing on that, but then doing my own thing with it. The tree was just because I came across a tree with a hole in it, and folklore is always about borders and liminal space, [thresholds]…passing things through things. What is true is that bodies would be passed out of windows sometimes, to prevent the spirit coming back through the door, but then I did add my own little bits.

11. And the Welden Valley, where the story is set…I did a bit of digging, but I couldn't figure out whether it was a real place or not.

It is a real place with a made-up name. When I was feeling fraught with writers block, at the end of that time, I was teaching an Arvon week at Lumb Bank, Heptonstall, and that tree is down in the valley beneath. It's where all of the mills were, just as I described in the book….that valley exists, but it's Heptonstall Valley, Hebden Bridge. I made up Welden - 'den' is like dean, or valley, and 'wel' is the proto-Indo-European root of the word that we take to be spiral now - if you think of the word 'whirl', it comes from the word 'wel'. I'm glad if it felt real, that's good.

Killing the Dead, the World Book Day book, is set in America in the early 60s and The Easiest Room In Hell is also in the US, this time in the late 20s; both books have a difference in voice but The Easiest Room in Hell had a, I want to say taste…I could taste the voice. Is that an OK way to put it? Was that a difficult thing to do, to somehow reorganize your brain to bring out these voices?

I think it was very helpful thing to do, to try and write those four parts with a different head on, because you want to make them all feel different; you don't want to have the same voice telling you another story. I think that was [a way] to make them all feel like that they were real, and because they are in different places, at different times, I thought they all need to feel - you said taste, and that is great - but feel, they had to feel different. I have done a few books in a diary style over the years…The Foreshadowing and White Crow are in that style as well.

I like the diary format because it is really interesting, [although] sometimes you run into such problems with the tenses, because it's like a continual floating past/present tense at the end of every day, when you report back. Sometimes it throws up big problems, and you have to avoid anything too clunky, but I think it was really helpful to have a different voice. It was like putting four different heads on and that helps keep them all distinct.

12. For me, The Easiest Room in Hell had a real signature voice, because it made me stop and try to figure out exactly where and when it was set, and find out about Poquatuck.

That is a real place, it is the old name for that part of Long Island. The Kirkbride thing is real, but there wasn't one of those hospitals there, I just decided that there ought to have been. I have done the drive right up to the North Fork and then taken the ferry and it just becomes quieter and quieter and more rural and poorer and poorer, until you finally get to that little headland, and I thought, this is where one of those hospitals should be.

13. There is what I'd call a strong structural skeleton binding these stories together - did you have a huge wall chart?

I had a plan of the four stories that are in Ghosts and I had already teed up what the links would be, the main things being using the phrase 'killing the dead', and having the full version of the poem that you get snippets of in Song of Destiny. But I didn't think I was going to do [the book] Killing the Dead for ages and then the chance came along to do it relatively soon. Once you've got those snippets - as long as you've got, as you say, that structure, that skeleton - then your flesh can go all around it in whatever way you see fit; as long as you don't need to move the nuts and bolts, you're okay.

14. Was there a physical chart, with lines and different colors?

Yeah, somewhat…when I did Midwinter Blood, I used these big sheets of paper and it really worked because you've got the seven circles for each part of the story with all of these lines going between them and little notes and things. Because that was seven [elements] and this was only four I didn't actually do so much planning. I had some diagrams and I found when I started them that it was OK, I knew what I was doing.

Those things are like comfort blankets [laughs]. If you need them, fine, but often I find they peter out towards the end because you think "Now I know what I'm doing". Other times I've stuck to it, having it hold my hand throughout the whole book.

15. For each of these stories you seem to have researched some arcane piece of history, science or mythology and in The Easiest Room it's medicine. There's some very interesting stuff talked about in the story, is it an area you're particularly fascinated by?

I like doing research. It's easier to do the research than to write the book. A lot of writers hate research and I don't understand it, because I only ever see it as a friend. If you're an academic writer, you have to read everything that has ever been written on the subject you're writing about and then you have to construct an argument, prove it - prove and reference everything you're saying, and you can't change the facts if you don't like them.

What we're allowed to do is just search through all these wonderful, mysterious, arcane things that people have discovered over the years, cherry-pick the things you like best, change them if they don't quite fit with what you're trying to do and stop reading at precisely the moment you get bored.

Mental health is something that has always interested me. I'm writing an adult novel at the moment that is set partially in an asylum in Paris at the end of the 19th century. I've been doing a lot of reading about the latter half of the 19th century and the changes in mental health provision, because at the beginning of that century it's basically still the medieval approach of incarceration - let's invent masks that prevent people from screaming. At the end of the century you've got people in Paris, Charcot, and Kirkbride in America, who were actually trying to do something to improve the lot of the mentally ill person. So I've been doing a lot of reading, and you come across really uplifting things, and then you come across really terrifying things - [like] this thing about infecting patients with malaria - and I just can't help using it in a book.

16. These details just add so much colour to a story.

In the past I wanted everything to be 100% accurate, like in The Foreshadowing - OK, apart from the fact that she sees the future, but all the stuff to do with the battle - and these days I think that's not what writing's about. We use the truth to our ends and if it is true, fine, and if it isn't then your made-up truth is telling, to be pretentious, a bigger truth.

Which neatly takes us to the final story, The Song of Destiny, which is set in the future. I thought, as I was reading your description what the future will be like, boy, you have high hopes for it!

[Laughs] I don't know…I needed to have high hopes for this part to work, because I wanted to have the mission to go and settle a new planet. That's the way that that part of the book starts: we've stopped believing, we have resolved our problems. And I am not saying I believe that at all, but I needed it to be that way for this story.

One thing I don't think will stop, until we wipe ourselves out, is the need to explore in the broader sense of the word. Again, back to the teenagers, a fundamental part of what it is to be human is to be curious and explore. To do things for the sake of it. Why do we want go to Mars? Why did we did we go to the moon? To beat the Russians? Yes, but it's what I was trying to get at, that the human need will continually be about voyaging and exploration.

17. Did it take you longer to invent the future than imagine the past in this project.

I think The Song of Destiny is probably the shortest part of the book, and yes, it did take a lot of thinking about; a lot of it, to be honest with you, was hard because of the numbers. And I'm saying this as someone with two Maths 'A' Levels. I was really going crazy trying to work the numbers out and in the end I got my daughter's boyfriend, who is a physics genius, to solve problems for me. It was quite hard, and there was a lot of reading about long-term space travel and the effect it has on the human body, although lots of it doesn't appear in the book. I wanted, as I said, for things being accurate - did you read Lord of the Flies when you were at school?

Sure.

Well, you know the part where they get Piggy's glasses and they use them to make fire? Our English teacher said to us "Of course you can't do this because Piggy is shortsighted, and you need longsighted glasses in order to make that work". If he hadn't said that, none of us would have noticed or cared, but that really has always bugged me because I know it could not happen.

I think we each have our own personal line, where we are happy for the rules to be bent, or where you say "No, I'm not buying that". It puts you off the story. I wanted to have the spinning spaceship, à la 2001, so that you have proper gravity, because you have so many serious sci-fi films - like Moon, with Sam Rockwell, which is very good, but when he's on the moon base he's in Earth gravity, not in moon gravity. He's not wearing gravity boots or anything, and it breaks my belief and that is a dangerous thing to break.

18. True. There is a contract between the author and the reader which is the suspension of disbelief. If you stretch that too far then the contract is null and void.

Absolutely, that's a good way of putting it, and the thing I find interesting about that contract is if someone is loving a book, they will let you get away with so much more. We have to do a lot more work initially, but if you get them on your side and loving the book, they will forgive quite a lot. Although, as I said, there is a line, and for me it's like Piggy's glasses.

19. So the science is pretty accurate in the book?

It should be, reasonably, yeah. If you can buy that we have invented a hyper-sleep system. But the mathematics, the distances and the times traveled [are all good]. I had been wrestling with this for months and I sent it to my daughter's boyfriend, and in one afternoon, in half an hour, he emailed back with this spreadsheet of what I had done wrong and how to fix things. Brilliant.

20. Is there any meaning behind the chapter numbering in The Song of Destiny, because I couldn't work it out.

It's the Fibonacci Sequence. The reason I did that is because the Fibonacci Sequence is connected to the spiral, through the Golden Ratio, the Golden Mean.

21. The spiral is something you reference a lot throughout the stories, and that the spiral has no end. But it does have a beginning, doesn't it?

If you draw a circle you have drawn the whole circle, If you draw a square you have drawn the whole square, but I think that with a spiral you are only ever drawing a shorthand for the whole thing. Does it start in the middle? Yes, it could do, or, equally, does it not regress into infinity in both directions? I really like that idea, the thought of a spiral disappearing in two directions.

22. I don't know why this occurred to me, but about halfway through The Song of Destiny I wrote down, "Who is Bowman?". Is he you?

Well, they're all me. I don't know if you agree with this, but I think every character you write somehow is a bit of you, or an imagined projection of you. There are other elements…when I am talking about Bowman drifting, that was something I was feeling very personally at the time, not when I wrote it but when I was creating him in my head, which was a few years before. That sense that you're always trying to get back to your past, but you can't because it is the past; instead, you have to go forward and you just start drifting, and maybe it's a good thing and maybe it's a bad thing.

This whole bit is my homage to Stanley Kubrick and 2001. So, Bowman's name is a composite of the character's name and the actor's name from the film - that is Kier Dullea is the actor, Dave Bowman is the character. Because I realized, at that point, I was writing something that had more than one similarity to the 2001 - it starts in prehistory and ends in the far future with an iconic symbol. In 2001 there's also the monolith, which is called a Sentinel, if you read the script, and that's why the Sentinel is everywhere in the book. It's just my way of putting my hands up and saying "I'm stealing from the greatest".

23. The reason I asked the question is that, as I was reading, he reminded me of you. And the questions he was pondering seemed to be very personal.

Okay. That's interesting. I take that one on the chin, Graham. I think the characters are all me, they're all personal in one way or another, but particularly the time I was developing Bowman in my head there was stuff I was feeling personally, and then you translate it into your fictional round.

Well, thank you for the amazing journey, Marcus, I enjoyed it a lot.

- ENDS -

The Ghosts of Heaven

The Ghosts of Heaven